Students write themselves into America

Twice a week this semester I shuffled through a crowded corridor and passed the door to “South Asia and the Institute: Transformative Connections,” a new exhibit at MIT. I was always intrigued by the sign, but never felt free enough to stop and look inside. I finally tried the door today, after an exam, but found it locked for winter break. Serves me right, I thought, for not making time for curiosity.

Looking online, I see that the exhibit was created by a group of historians at MIT who were interested in the surprising story of South Asian students at MIT. Did you know that a man named Keshav Bhat enrolled at MIT as early as 1880? In a video reflecting on the project, a student talked about seeing herself in the yearbook photograph of the first South Asian woman to attend graduate school at MIT. “She is the first of me,” she says beaming.

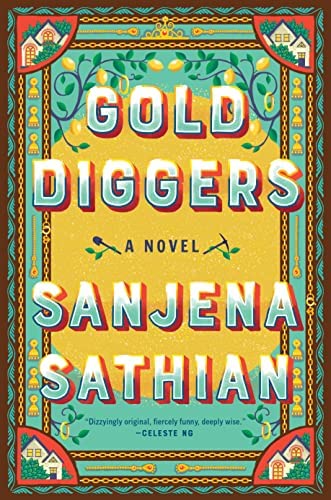

Her words reminded of a recent novel, Gold Diggers by Sanjena Sathian. In the novel Neil, a second-generation Indian immigrant, studies history at Berkeley and becomes fascinated with the story of a “Bombayan” who made it to the California gold rush in 1850. The story is a revelation to him, a first glimpse of self-recognition in the past, the same glimpse the MIT student in the video saw. “If I had roots in American soil,” wonders Neil, “if we had not all so recently crossed oceans, if our collective past was more textured than I’d been led to believe, then, well, maybe there were other ways of being brown on offer.”

Neil imagines this unnamed immigrant using his gold fortune to start a publication. “Who would suspect a professional writer of English to be an outsider?” he whispers to the Bombayan, “Make use of all you took. Write yourself into America.” Then his theory crumbles; he finds a curt newspaper clipping on the “Bombayan’s” brutal murder in a mining camp. “I would never have a corollary in the past,” he mourns, “never have a legible American ancestor to provide guidance on how to make a life.”

But sometimes reality out-inspires fiction. The MIT historians had much better luck than Neil: guided by Ross Bassett’s The Technological Indian, a comprehensive study of Indian MIT students from 1880 to 2000, they managed to track down and interview hundreds of “corollaries in the past.” You could say that in capturing and curating this history, these students write themselves into America. I’m thinking about them now, and that crowded corridor—imagining it packed with the past—Keshav Bhat shuffles past and gives that same look of recognition—I marvel at how a university’s students can be so tangled in time, so situated in space.