Thumbprints on the glass

On Saturday morning I walked into MIT’s List Arts Center to plan a heist of sorts. Yes, really, walked into— as I approached the List I collided headfirst with the clear glass revolving door, fell to the sidewalk with a bloody face, and stumbled another block or so to MIT Medical to have the wound tended to. When I passed by that now-less-clean door on my way home that evening, still in good spirits but with a bandaged eyebrow, the museum staff breathed a collective sigh of relief.

I came back on Wednesday to finish the job. The plan was to walk in, step up to a work of art, grab it off the wall, and take it home— all on the up-and-up, as part of the List Center’s Student Lending Art Program. The program offered me, and a few hundred other MIT students, the chance to choose one original work to keep for the year.

Try this the next time you visit a museum. Imagine being granted one piece to take home with you, for keeps. How would you choose? Let me just tell you, it’s harder than it sounds. A work of art is innocent enough when you pass by it in a crowded exhibit. But when you picture waking up day after day by it, seeing it through your bleary eyes on your best and your worst mornings, it begins to seethe with valence. Renown and objective value fall away; the million-dollar Picasso, formerly a curiosity, turns unbearable or even nauseating when you imagine coming home to it night after exhausted night.

So there I was, pacing circles into the List, almost out of time. More than one staff member was asking me if I needed help. Maybe I did need help. But then I spotted something remarkable. I am a little ashamed to say, it wasn’t a work of art— it was a label, that said:

Nicole Eisenman

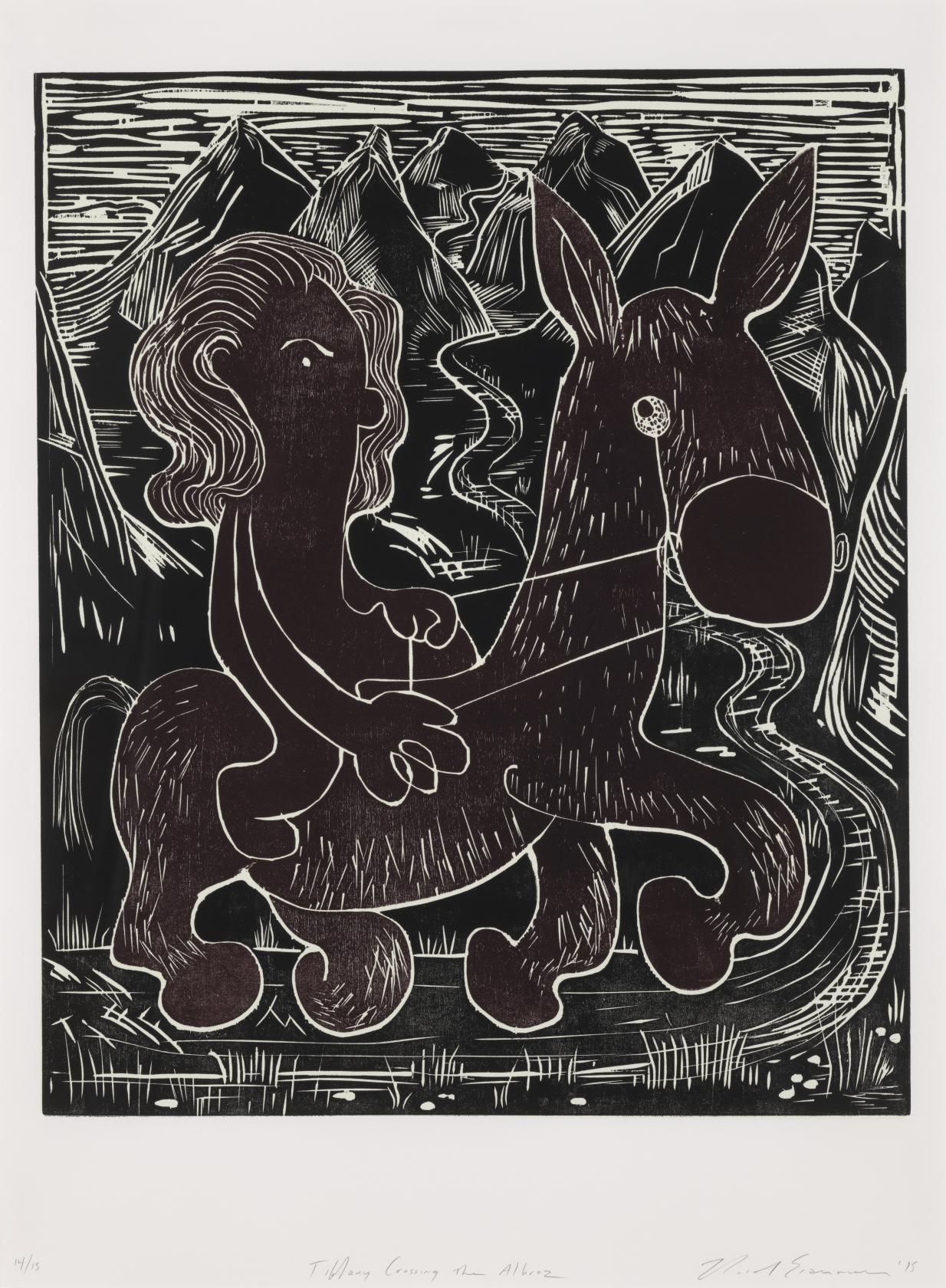

Tiffany Crossing the Alborz (2015)

Medium: Glow in the Dark woodcut

Glow-in-the-dark ink! How could I not? With the trespass of a first kiss, I reached out, touched the frame, and pulled it clumsily off the museum wall. (I’d better not make that a habit, I thought, as I noticed the white splotches my thumbprints left on the pristine glass case.)

It took me half an hour to walk the artwork home. I felt ridiculous and clumsy with my awkwardly-sized donkey doodle, but at the same time very conscious that nobody was paying any attention to me. I guess out on the street in the sunlight, it’s hard to know what is and isn’t a museum piece, what is and isn’t a cheap poster or student scribble mounted in a cheap frame. Maybe the thieves who robbed the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum just strolled through Boston Common with their stolen works in their arms— like Nicholas Cage with the Declaration of Independence in National Treasure— would anyone know? Would anyone care?

Tiffany and her steed (—or is she the steed?—) sat by my bed for days before I worked out how to hang her up on the wall. As promised, she glows in the dark: green, but soft, like the faintest neon sign. It’s a sight not many have seen; after all, you can’t just ask a museum to dim the lights for you. At night, when I finish working, I brush my teeth and turn off my lamp, and she suddenly pops from mild-mannered Jekyll to green-glowing Hyde. She guides me to my bed, being the only thing my eyes see in an otherwise dark room, luminous but not quite luminous enough to cast light on anything else I own. When I wake up, she is back to her paper self. As much as the sun or moon, her rhythms infiltrate my own.

She has started reminding me of Don Quixote, which would make me Sancho Panza, and isn’t that what it means to live beside a work of art? To be pressed up against the interface between two realities, to mediate that frontier as epistemological umpire? Blood on the door, flicker of the lamp, thumbprints on the glass— it’s a lot of responsibility, a lot of pressure. I am glad for that frame, I think to myself, glad for that invisible boundary, without which I would surely be sucked into Tiffany’s world, surely be deposited shivering at the foothills of the Albroz.